2022-2023 Flu Season Predictions: Can They Tell Us What’s Next?

Reviewing early forecasts and assessing flu trends to date

Since COVID-19 made its appearance, questions soon arose over how mitigation measures for COVID-19, such as masking and social distancing, might affect the seasonal patterns and transmission of other seasonal respiratory viruses. Some mathematical models forecast a potentially disastrous 2021-2022 flu season, depending on whether the high annual flu vaccination levels recorded in the 2020-2021 season continued.

Although the 2021-2022 flu season proved relatively mild, these predictions of heavy flu activity became more accurate at the outset of the 2022–2023 flu season. Speculation about a “twindemic” involving seasonal influenza and COVID soon turned to talk of a “tripledemic” involving seasonal flu, COVID and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).

Now that we are several months into the flu season—how have these early predictions of a very severe flu season panned out so far?

Fall 2022: Flu returns in full force

As it has turned out—so far, this year’s flu season has aligned with 2022-2023 flu season predictions. These were based in part on the most recent Southern Hemisphere flu activity; Chile and Australia, for example, experienced flu seasons that began and reached a peak earlier than is typical. (The Southern Hemisphere flu season typically runs from April to September, whereas the Northern Hemisphere season usually spans from October to April or May.

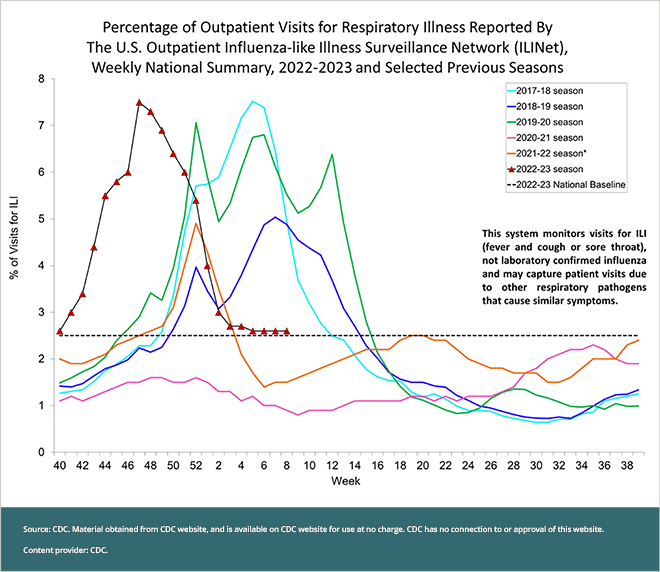

Looking back, the Southern Hemisphere experience seems to have been a good predictor of what happened here—at least in terms of the early months of the flu season. Flu activity in the United States started about six weeks earlier than usual, before many people were vaccinated. Outpatient visits for influenza-like illness reached a peak in November 2022, weeks earlier than the last five flu seasons; the majority of these outpatient visits were made by children aged 0 to 4 years old, followed by people aged 5 to 24 years old (see chart). Hospitalizations due to influenza reached a peak in the week ending December 3, 2022, with most occurring in adults aged 65 and older, followed by children ages 0 to 4 years old.

To put this information into perspective, the early, heightened flu activity during the 2022-2023 flu season has rivaled some of the worst flu seasons in the last 10 years. For example: During the 2014-2015 flu season, considered a moderately severe season, the highest levels of hospitalizations saw nine out of every 100,000 people hospitalized for confirmed influenza infection. By comparison, during the current flu season, hospitalizations with confirmed flu peaked the week of November 28, 2022; 8.7 people out of every 100,000 were hospitalized with confirmed influenza.

The heightened activity observed this flu season is a major shift from the last two flu seasons. During the first full flu season of the COVID pandemic—from 2020 to 2021—flu circulated at historically low levels in the United States. The following season in 2021 to 2022 saw an uptick in influenza activity from the prior year but still less than in the most recent seasons.

These unusually low levels of influenza cases and hospitalizations coincided with widespread COVID mitigation measures such as masking, remote working and social distancing. Notably, 2020-2021 saw peak levels of flu vaccination, which may have also contributed to the reduction in flu illnesses recorded that year. Unfortunately, flu vaccination rates decreased in the 2021-2022 flu season.

In this season, flu vaccination rates were low enough in the fall to cause the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to post a video on CDC social media channels, urging those who remained unvaccinated to get their flu shots. (Also, because flu began circulating earlier than usual, many people who wait until a little later in the fall for a flu shot may not have been vaccinated at that point—so that may have contributed to the higher numbers of flu cases and hospitalizations observed in the early months of the flu season.)

At present, flu vaccination rates among various age groups and are now similar to last season, although rates for pregnant people are notably lower (46.5% for the 2022-2023 flu season, compared with 56.3% in 2021-2022).

Flu season burden: Preliminary in-season estimates from the CDC

|

|

| Flu illnesses | 25 million — 51 million |

| Flu medical visits | 12 million — 25 million |

| Flu hospitalizations | 280,000 — 630,000 |

| Flu deaths | 18,000 — 55,000 |

| Pediatric flu deaths | 106 |

These preliminary estimates are calculated based on data collected through CDC’s Influenza Hospitalization Surveillance Network (FluSurv-NET).

Late fall/early winter 2022: The “tripledemic” arrives

Of course, influenza was not the only virus that returned in full force this fall—albeit earlier than usual, with higher-than-usual cases and hospitalizations—but so did respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and other respiratory viruses. In October and November, the sudden increase in seasonal flu and RSV cases, overlaid onto the COVID landscape, created a “tripledemic” that strained healthcare resources, which in turn had already been stretched thin. As of early 2023, seasonal flu cases and hospitalizations have subsided, while RSV cases remain high. COVID has continued to circulate throughout the fall, too, although reported cases are far lower than those recorded a year ago.

Ultimately, the co-circulation of multiple respiratory viruses throughout the 2022-2023 flu season may have been inevitable with reductions in COVID mitigation measures, children returning back to school and more people resuming travel plans. The reduced exposure that people have had to influenza due to low flu activity and lower rates of flu vaccination in recent years may have helped reduce population immunity to the flu, thus contributing to the unusually early and high numbers of flu cases seen earlier this season.

Focusing on influenza alone—as mentioned earlier, flu activity has declined in recent weeks, with fewer patients admitted to hospitals with influenza since numbers peaked in the fall. Seven of 10 regions that track flu and COVID data across the country have recorded outpatient respiratory illness rates below their baselines. Looking at recent national trends in these rates (see chart), it’s possible that they may remain low—even dipping below baseline—although the season may extend into the spring months.

Early 2023: An uncertain outlook for this winter and spring…and summer?

With this current flu season well under way, what can we potentially expect to see?

Recent Northern Hemisphere flu season history provides some possibilities to consider. As noted earlier, the previous 2021-2022 flu season was considered mild; it also saw two separate waves of flu. (Influenza activity has peaked two to three times during three of the last five flu seasons.) A higher percentage of positive clinical laboratory test results and more hospitalizations were recorded during the second wave than in the first. Notably, the flu season also saw a later peak of flu activity that stayed at higher levels late in the season—from late April through early June—compared with previous seasons.

Here in the United States, recent CDC reports indicate that the majority of influenza strains detected in lab tests here have been caused by Influenza Type A—specifically, Influenza A(H3N2); however, the appearance of another strain may create a new peak of infections. As of February 10, Influenza A(H3N2) currently makes up 54.2% of the Type A cases detected in the lab, while Influenza A(H1N1) comprises 45.8% of the other Influenza A cases. These strains appear to be a good match for the antigens contained in this season’s flu vaccine. If the circulating strains mutate enough, or new strains start circulating, it could cause a new wave of illness.

Twice a year, the World Health Organization (WHO) meets with laboratories and other organizations to assess determine the composition of flu vaccines for the upcoming flu seasons in each hemisphere. This information is used to guide vaccine manufacturers in vaccine development each year. For this season, flu vaccines were designed to protect against one Influenza Type A(H1N1) virus, one Influenza Type A(H3N2) virus, one Influenza B/Victoria lineage virus, and one Influenza Type B/Yamagata lineage virus.

How to handle potential new flu waves in 2023…and beyond

While gauging the future of the current flu season is a challenge, doing everyday things to limit the spread of the flu virus can help. As we know from the past few years living with COVID, non-pharmaceutical interventions, such as limiting exposure to people who are sick and washing your hands, are valuable in stopping the spread of germs.

The CDC maintains a robust surveillance system to monitor influenza activity, so should cases rise again, the agency will alert the public, just as it did earlier in the season. In the meantime, getting a flu vaccine remains the best action you can take to protect yourself from the flu, as well as others who are at higher risk of complications. All people who are aged 6 months and older and are eligible to receive a flu vaccine should get one if they haven’t already, as long as flu activity continues this season. Even if you have had the flu already, getting a flu shot may keep you from getting influenza from another flu strain. So it’s a still a good idea to get your flu vaccine even after you’ve had the flu…and even if you’re wondering if it’s too late to get a flu shot (it’s not!). And if you do catch the flu, there are prescription antiviral drugs that can be used to treat your flu illness. They should be started as early as possible.

Read more about flu prevention